What does utility frequency mean?

Definition

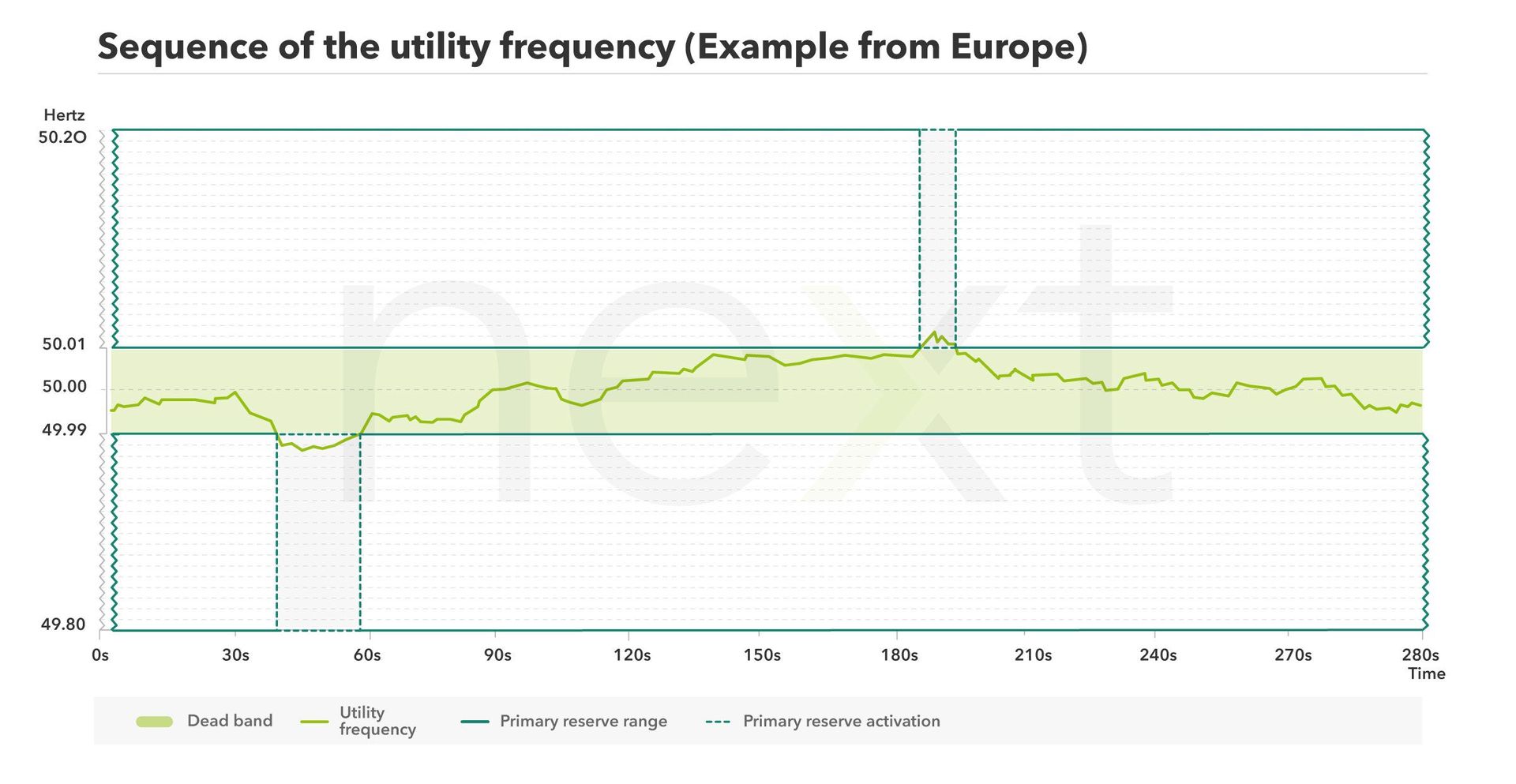

It is well-know that household alternating current (AC) in Germany and Europe has a frequency of 50 Hertz (Hz), while other parts of the world run on 60 Hz. What is less known is that this utility frequency (also known as mains frequency or grid frequency) also provides information about the ratio of electricity generation to electricity consumption in a power grid. If the frequency drops too low, there is not enough electricity in the grid; if the frequency increases too much, there is too much electricity in the grid. An intelligent supply-demand mechanism and a functional system for ancillary services to compensate for frequency deviation is necessary to keep the utility frequency at a stable 50 or 60 Hz.

50 Hertz vs. 60 Hertz

Around the world, most regions that utilize alternating current have a nominal utility frequency of either 50 Hz or 60 Hz. This difference is mainly historical and can be traced back to the very beginnings of electrification. At that time, technical and logistical factors meant a frequency of 60 Hz made the most sense for the United States. In Germany, the reference value of 50 Hz is said to go back to AEG founder Emil Rathenau. Starting from Berlin, the nominal value expanded and gradually became the standard. Even in the 1940s, different frequencies – sometimes within a country – were not uncommon. Today, most countries use a utility frequency of 50 Hz, but a full global conversion to either 50 or 60 Hz is currently not a viable economic option. Japan, Saudi Arabia, and South Korea have even more complicated scenarios in which both network frequencies are used.

Countries with 60 Hz

- Antigua and Barbuda

- Aruba

- Bahamas

- Belize

- Bermuda

- Brazil

- Canada

- Cayman Islands

- Colombia

- Costa Rica

- Cuba

- Curaçao

- Dominican Republic

- Ecuador

- El Salvador

- Guam

- Guatemala

- Guyana

- Haiti

- Honduras

- Liberia

- Mexico

- Nicaragua

- Panama

- Philippines

- Puerto Rico

- St. Kitts and Nevis

- Taiwan

- Trinidad and Tobago

- United States

- Venezuela

Countries with 50 Hz

- Afghanistan

- Albania

- Algeria

- Andorra

- Angola

- Anguilla

- Argentina

- Armenia

- Australia

- Austria

- Azerbaijan

- Bahrain

- Bangladesh

- Barbados

- Belarus

- Belgium

- Benin

- Bhutan

- Bolivia

- Bonaire

- Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Botswana

- Bulgaria

- Burkina Faso

- Burundi

- Cabo Verde

- Cambodia

- Cameroon

- Central African Republic

- Chad

- Chile

- China

- Comoros

- Congo

- Côte d'Ivoire

- Croatia

- Cypress

- Czech Republic

- Denmark

- Djibouti

- Dominica

- Egypt

- England

- Eritrea

- Estonia

- Ethiopia

- Faroe Islands

- Fiji

- Finland

- France

- Gabon

- Gambia

- Georgia

- Germany

- Ghana

- Greece

- Greenland

- Grenada

- Guadeloupe

- Guinea

- Hong Kong

- Hungary

- India

- Indonesia

- Iran

- Iraq

- Ireland

- Iceland

- Israel

- Italy

- Jamaica

- Jordan

- Kazakhstan

- Kenya

- Kuwait

- Kyrgyzstan

- Laos

- Latvia

- Lebanon

- Lesotho

- Libya

- Lichtenstein

- Lithuania

- Luxembourg

- Macau

- Macedonia

- Madagascar

- Malawi

- Malaysia

- Mali

- Malta

- Martinique

- Mauretania

- Mauritius

- Moldova

- Monaco

- Mongolia

- Montenegro

- Morocco

- Mozambique

- Myanmar

- Namibia

- Nepal

- Netherlands

- New Zealand

- Niger

- Nigeria

- Norway

- Oman

- Pakistan

- Papua New Guinea

- Paraguay

- Poland

- Portugal

- Qatar

- Romania

- Rwanda

- Russia

- Samoa

- Scotland

- Senegal

- Serbia

- Seychelles

- Sierra Leone

- Singapore

- Slovakia

- Slovenia

- Solomon Islands

- Somalia

- South Africa

- Spain

- Sri Lanka

- St. Lucia

- St. Vincent and the Grenadines

- Sudan

- Swaziland

- Sweden

- Switzerland

- Syria

- Tajikistan

- Tanzania

- Thailand

- Tunisia

- Turkey

- Turkmenistan

- United Arab Emirates

- Uganda

- Ukraine

- Uruguay

- Uzbekistan

- Vietnam

- Wales

- Yemen

- Zambia

- Zimbabwe

More to read

What is happening from a technical point of view? Fundamentals of AC operation

As the name suggests, alternating current changes its polarity continuously. This is achieved by generating a voltage force between two oppositely charged poles. Charged particles are set in motion between the poles for current to flow. This is the electrical voltage; it is the basic requirement for electricity to flow at all. A higher difference between the charged poles results in higher electrical voltage, which is measured in volts (V). Higher voltage leads to a higher electrical output. The following formula applies:

P (electric power) = V (electric voltage) *A (electric current)

A closely interconnected grid operated by alternating voltage requires a steady frequency that is largely constant over time. The frequency denotes how often the polarity changes between two points.

Practical use of the utility frequency: time signal for clock radios

The interconnected European grid now only experiences minor deviations from the nominal value of 50 Hertz. However, as recently as the 1980s in the former German Democratic Republic, it was by no means uncommon for the utility frequency to drop by one or two Hertz on days with lower electricity generation. Even today, small deviations in the utility frequency have very practical consequences: Utility frequency is used as a time signal for simple electronic devices such as clock radios. In the spring of 2018, a drop in the utility frequency throughout Europe led to many delays in schools and offices, as the low utility frequency caused clock radios to run slower and sound their alarms later.

However, according to a press release from the Association of Transmission System Operators ENTSOE-E, these utility frequency deviations were not caused by specific physical or technical issues in the electricity grid, but by a political dispute between Serbia and the Autonomous Republic of Kosovo. Currently, 113 GWh of unsupplied electricity remain uncompensated. According to the ENTSOE-E press release, a political compensation solution is still pending.

Calculation of the utility frequency

The utility frequency, specified in Hertz, is calculated from the polarity changes per second, which are expressed in voltage waves. At a utility frequency of 50 Hz, a total of 50 voltage waves occur per second, with the voltage changing polarity 100 times.

Since it is difficult to store electricity in the grid, there must be a balance between production and consumption for the power supply to function properly. If the utility frequency deviates from the nominal value, it is the result of either a surplus or shortfall of electricity. This makes the utility frequency a reference value for available power in a given moment.

Only minor deviations from the 50 Hz nominal value are possible in the European power system, meaning intervention by network operators occurs with decreasing frequency. Nevertheless, ancillary services are constantly standing by to rebalance any discrepancies that may occur. Increased use of renewable energies can theoretically lead to greater frequency fluctuations, but as past years have shown, this does not necessarily impact grid stability (as referenced in the SAIDI index).

Disclaimer: Next Kraftwerke does not take any responsibility for the completeness, accuracy and actuality of the information provided. This article is for information purposes only and does not replace individual legal advice.