What is a PPA (Power Purchase Agreement) ?

Definition

A Power Purchase Agreement (PPA) often refers to a long-term electricity supply agreement between two parties, usually between a power producer and a customer (an electricity consumer or trader). The PPA defines the conditions of the agreement, such as the amount of electricity to be supplied, negotiated prices, accounting, and penalties for non-compliance. Since it is a bilateral agreement, a PPA can take many forms and is usually tailored to the specific application. Electricity can be supplied physically or on a balancing sheet. PPAs can be used to reduce market price risks, which is why they are frequently implemented by large electricity consumers to help reduce investment costs associated with planning or operating renewable energy plants.

Table of Contents

- Why PPAs?

- How do PPAs and renewable energy financing work together?

- What happens to PPAs after the subsidy period expires?

- Who concludes PPAs?

- What are the different types of Power Purchase Agreements?

- Physical PPAs

- Synthetic PPAs (also: Virtual PPAs)

- What are the Advantages of Power Purchase Agreements?

- What are the Disadvantages of PPAs?

Why PPAs?

Depending on regulation and the market environment, different situations can arise in which PPAs are an advantageous form of financing or a stabilizing factor in long-term power delivery.

How do PPAs and renewable energy financing work together?

In some countries, Power Purchase Agreements are already being used to finance construction (investment costs) and operation (operating costs) of renewable energy plants. Countries in which utilities are required or would like to cover parts of their electricity supply with renewables are particularly drawn to PPAs. The agreements represent an alternative opportunity for expanding renewables to areas where politicians are hesitant to push forward with renewable energy expansion (and subsidization).

What happens to PPAs after the subsidy period expires?

If a statutory subsidy expires on an existing power plant, PPAs are a way of ensuring follow-up financing for the plant’s operation. This could include operating costs such as maintenance and leasing.

Who concludes PPAs?

Power producers conclude PPAs either bilaterally with a consuming company ("Corporate PPA"), or with an electricity trader who purchases the electricity produced ("Merchant PPA"). The electricity trader may continue to supply power to a specific electricity consumer (turning the contract back into a "Corporate PPA"), or may opt to trade the power on an electricity exchange.

Many international corporations already purchase shares of their electricity consumption via PPAs or have stated their intention to do so more frequently (click here). They use PPAs to obtain stable and calculable electricity prices.

PPAs are an effective way to reduce electricity price risk, especially for operators of plants with high investment and low operating costs (such as PV and wind turbines). With payment for the electricity already secured to a certain extent, plant operators and financing banks can feel more confident that proceeds from electricity sales will indeed cover investment costs. This makes the project more profitable in the long run.

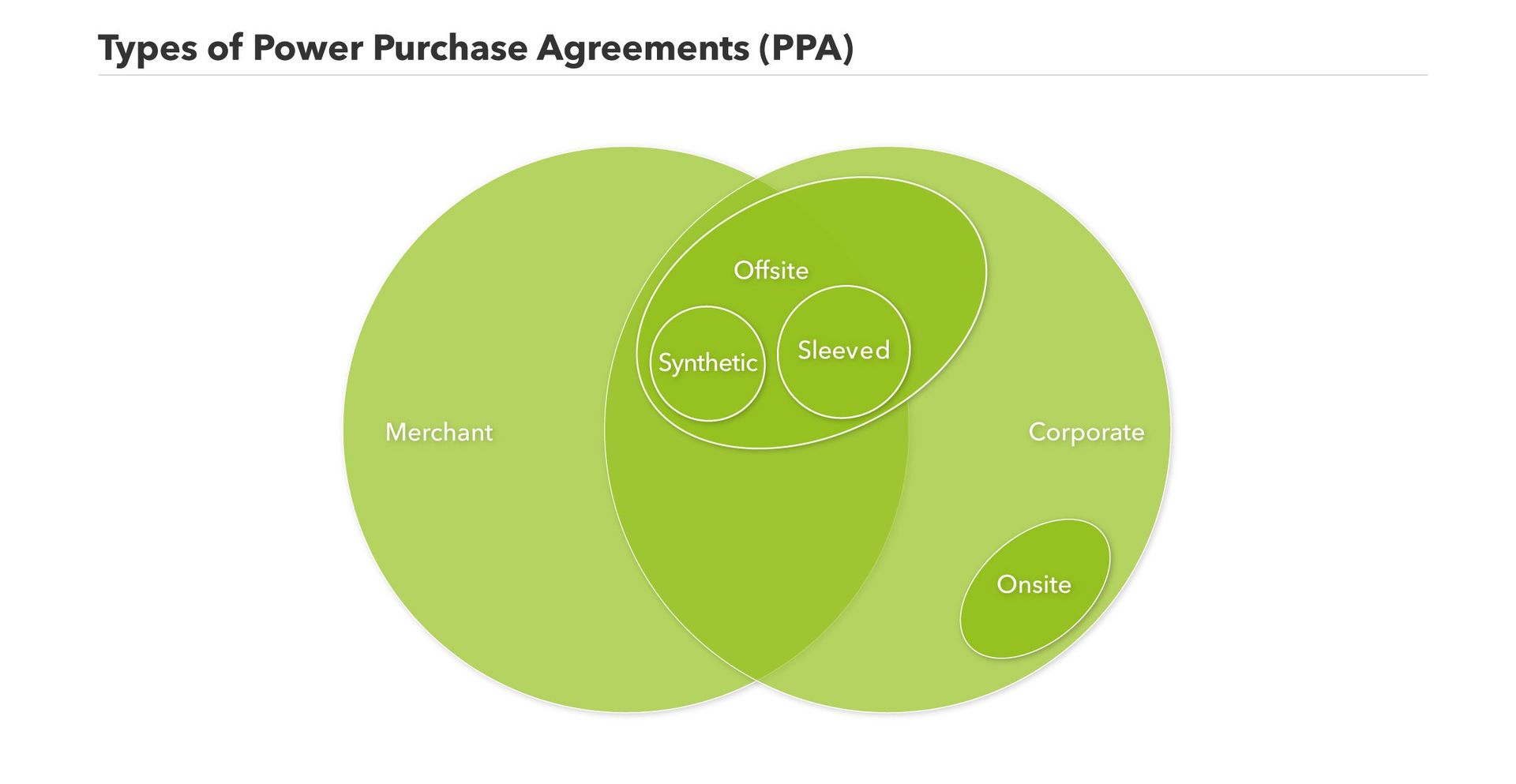

What are the different types of Power Purchase Agreements?

It is difficult to fully define the different types of PPAs due to the wide range of possible and practiced contractual arrangements. In addition, different PPA characteristics cannot be clearly defined in a single system. All the same, we’ll attempt to provide an overview:

Physical PPAs

There are three types of physical PPAs, with some overlap among them. Common to all three is a fixed quantity of electricity that is sold and supplied in the PPA. The only difference is how the electricity is supplied.

- On-site PPA: An on-site Power Purchase Agreement is a direct physical supply of electricity, necessitating physical proximity of plant and consumer. An on-site PPA means that the generation plant is located behind the metering point of the consumer, and may even be at the same location (on-site at a company, for instance).The consumption profile of the consumer usually dictates the specific installation and also the parameters of the PPA. The grid operator is involved to the extent that residual electricity can be supplied to the grid. Since the electricity generated by an on-site PPA directly reduces a company's consumption, all on-site PPAs are also corporate PPAs. For example, an industrial company with a suitable roof on its premises might like to reduce its electricity procurement costs but is not willing to take on the installation of a photovoltaic system on its roof. Instead, the company opts to outsource the project (and the financial and operational risks). For this purpose, the company enters an on-site PPA with a project planner, who now installs the photovoltaic system on the roof and sells the electricity generated directly to the company.

- Off-site PPAs: Off-site PPAs do not constitute a direct physical supply of electricity between the plant and a nearby consumer. It is merely an agreement to purchase a physical quantity of electricity as defined in the PPA. In contrast to on-site PPAs, the producer delivers the electricity to the consumer through the public grid. This requires an additional settlement via the balancing groups of the electricity generating plant and the consumer. The power generation plant does not need to be located close to the consumer. This provides additional flexibility, as the plant operator can now choose locations with optimal conditions or a plant that already exists. A single plant can also enter into several Power Purchase Agreements with different customers, who are credited their share of the electricity production via their balancing groups. The price for the electricity supply is negotiated in the PPA, meaning all participants have long-term price security. If applicable, charges and grid fees still need to be paid to the grid operator.

- Sleeved PPA: A sleeved PPA is simply an off-site PPA in which an energy service provider takes on various processes and acts as an intermediary between producer and consumer. It might provide the following services: balancing group management, aggregating various electricity producers to its portfolio, supplying residual quantities of electricity or selling surplus quantities, preparing feed-in forecasts, marketing green certificates, or assuming various risks (such as balancing energy costs or default / insolvency risks of a contractual partner).

More to read

Synthetic PPAs (also: Virtual PPAs)

Synthetic PPAs decouple the physical flow of electricity from the financial flow. This allows for even more flexibility in contractual arrangements. In the case of synthetic Power Purchase Agreements (also known as SPPAs), producers and consumers agree on a price per kilowatt-hour of electricity, just like a physical PPA. However, the electricity is not supplied directly from the energy generating plant to the consumer. Instead, the producer’s energy service provider (such as an electricity trader) takes the produced electricity into its balancing group and trades it (on short-term power markets, to name one example). The consumer’s energy supplier (such as a municipal utility) procures precisely the feed-in profile supplied by the producer to its energy service provider on behalf of the consuming PPA partner, with procurement occurring on a platform such as the spot market.

In the synthetic PPA, this electricity flow is now supplemented by what is known as a contract for difference. In this contract, the PPA contract partners aim to compensate for the difference between the agreed PPA price and the actual spot market price. This means each contractual partner in the PPA has two payment streams: one with the respective energy service provider and one with the PPA contractual partner. In each case, the payments add up to the PPA price defined at the beginning and provide both sides with the desired price security.

Without direct physical delivery between the contracting parties (like an on-site PPA), and with no direct balancing sheet link between them (like an off-site PPA), this represents a simple and administratively low-cost PPA. It is well-suited for cases when a producer does not manage or wish to establish its own balancing group, to name one example.

What are the Advantages of Power Purchase Agreements?

The advantages of a Power Purchase Agreement include long-term price security, opportunities to finance investments in new power generation capacities, or the reduction of risks associated with electricity sales and purchases. In addition, a specific physical supply of electricity with certain regional characteristics and guarantees of origin can occur. Customers can use this opportunity to make their brand more sustainable and greener.

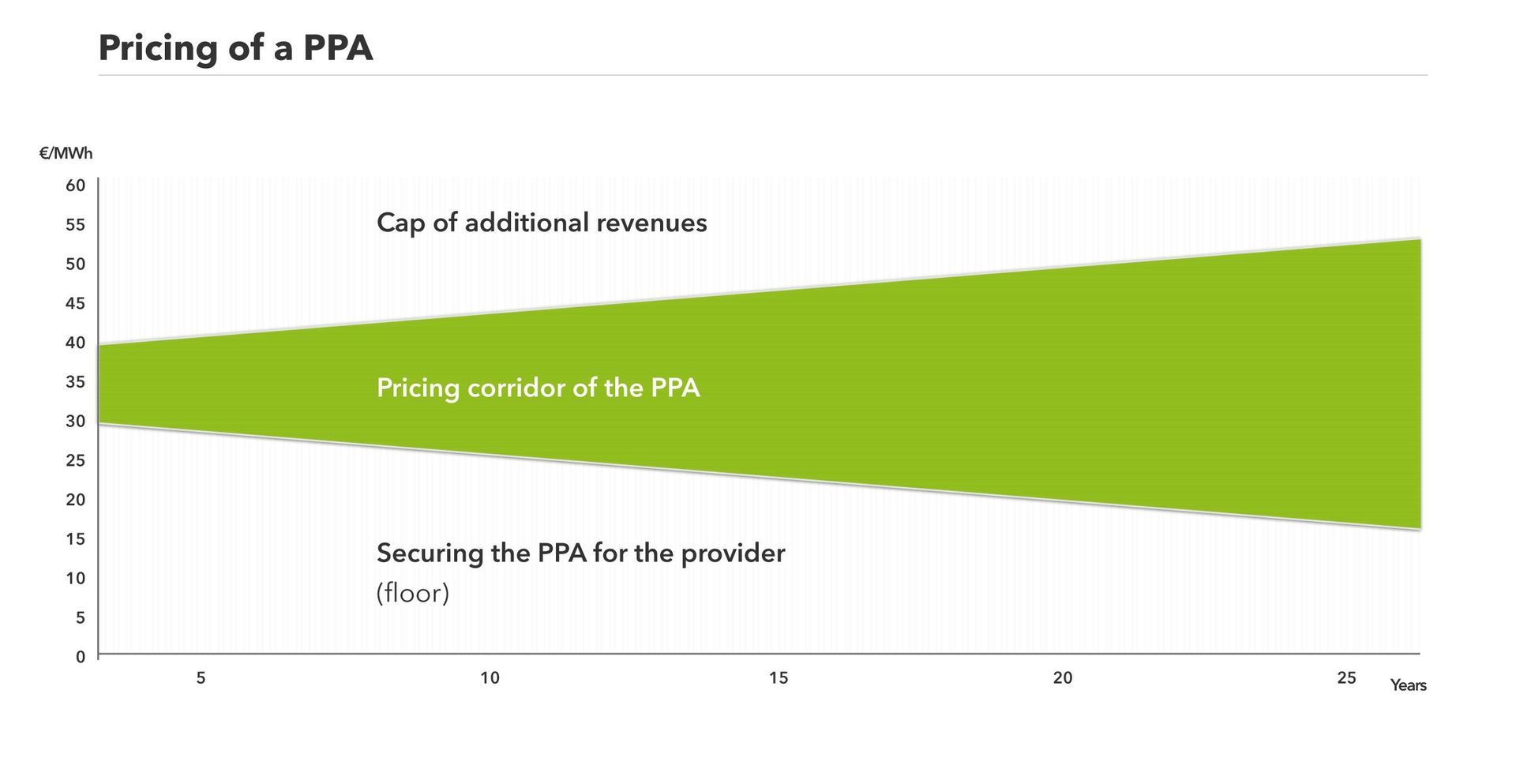

The open-end of the contract’s design also creates a great deal of leeway to reflect preferences of individual plant operators and electricity consumers. This also applies to pricing: PPAs can be signed at fixed prices, or can allow for greater participation in market risks and opportunities.

What are the Disadvantages of PPAs?

PPAs are complex contracts and often require a great deal of time and negotiation prior to conclusion. The long-term nature of PPAs can be a disadvantage in the event of price developments that end up being negative for one party. Furthermore, electricity production itself – especially from wind and photovoltaics – can fluctuate. If the quantities of electricity – agreed upon well in advance – are not available at the time of delivery, the plant operator must provide financial or physical compensation, or outsource to a third party such as an electricity trader.

Disclaimer: Next Kraftwerke does not take any responsibility for the completeness, accuracy and actuality of the information provided. This article is for information purposes only and does not replace individual legal advice.