What is Power Trading?

Definition

Power trading refers to purchasing and selling power between participants in the energy industry . Various forms of power trading are possible depending on the market design, ranging from short-term trading to long-term power purchase agreements.

History of power trading

One of the earliest forms of an energy market emerged in 1980, when Chile privatized its power industry. Other Latin American countries, such as Argentina, followed suit in the early 1990s and adopted elements of Chile’s newly-liberalized power sector. In 1990, England was the first European country to establish a liberalized power trading market, and its model was adapted for other Commonwealth countries. Even though the English market predated a European market, the European Commission was already working on plans for a European energy market in the 1980s. The aim was to create market driven by competition. During the 1990s, several European countries began liberalizing their power markets, which included efforts to unbundle power generation and distribution. The European Green Paper of 1995 played an important role in establishing the liberalization of the European energy landscape as a directive for the years to come. The next step came in 2000, when the Lisbon Strategy transformed this idea into actual policy. This triggered the creation of energy markets in the EU and established a rough road map for moving forward.

Today, market coupling enables cross-border trading, allowing several European countries to trade on the same power exchanges.

Historically in the United States, vertical integration in the energy industry meant there was less of a need for a dedicated energy market. This has slowly changed since the early 2000s, especially in the aftermath of the Californian electricity crisis in 2000. However, there are still distinct conceptual differences between individual states. Prior to market liberalization, the energy industry was essentially vertically integrated everywhere in the world. Electricity systems – from generation, to power sales, to the end-user – were generally state-owned or operated by private companies under government regulation. This meant there were hardly any markets for electricity. Potential shortages and surpluses in power were sold bilaterally. All power produced and consumed is noted in a balancing group, which also manages the balancing act between power feed-in and off-take (these must be equal). Forecast deviations in consumption and production are evened out using short-term trading. Please refer to our article on balancing groups for more details.

Different market types

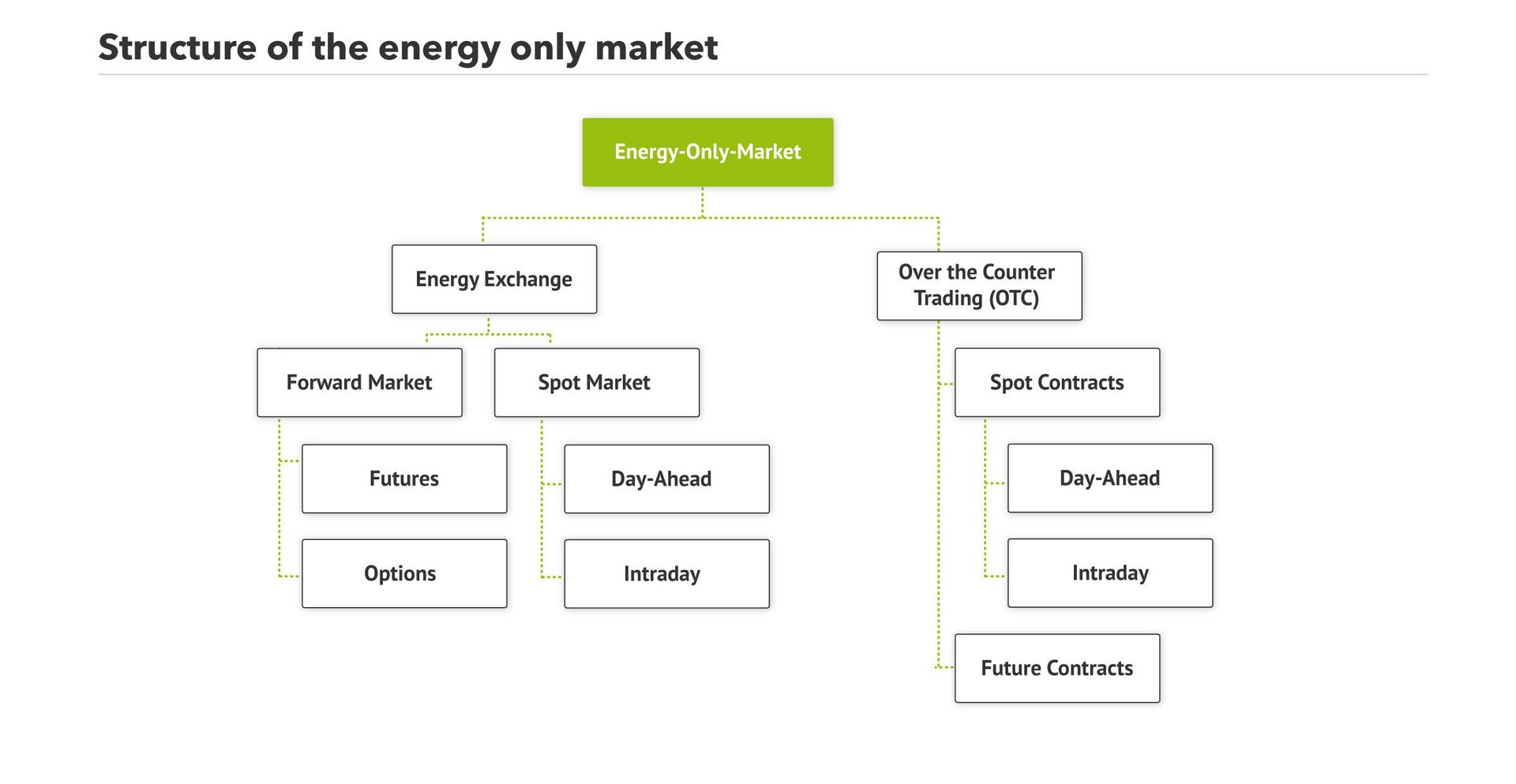

Power is traded on different marketplaces. In general, the power delivery timeframe and the form of the transaction characterize how the marketplaces are defined. Since power cannot yet be stored in large quantities, power trading is conducted using either short-term trades or long-term agreements, in which the power has yet to be produced.

OTC

In OTC (over-the-counter) trading, power is directly traded between two parties, with prices and trading volume agreed in bilateral negotiations. OTC trading is the most common form of power trading, especially in the conventional power industry. It is less common in the renewables industry. Read more here.

Power purchase agreement

A power purchase agreement (PPA) often refers to a long-term electricity supply agreement between two parties, usually a power producer and a customer (such as an electricity consumer or trader). A power producer is usually seeking long-term income with a PPA, while a power consumer is seeking long-term power provision. For a more detailed overview, have a look at our PPA article.

Short-term power trading

In today’s power trading, power exchanges are common – especially in Europe. While participants on the exchanges trade anonymously, the exchange’s general framework provides a transparent system for multilateral trading. Power exchanges operate in a similar way to regular stock exchanges. A typical type of power exchange is a short-term spot market. This includes markets such as the day-ahead and the intraday market, where power is traded for either the upcoming or current day. The largest spot exchanges in Europe are the EPEX Spot and the Nord Pool, but there are also several local markets. The EPEX Spot is the spot-market exchange for Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Switzerland and the United Kingdom. The Nord Pool is the spot market for Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Norway, Sweden and the United Kingdom. To ensure better market coupling and to allow cross-border intraday trading, EPEX Spot, Nord Pool, GME and OMIE established a harmonized trading system called XBID.

These exchanges are used to buy and sell power on short notice to meet demand. Usually, these transactions are needed to level out forecast deviations in both consumption and production. For example, a large-scale power consumer such as a utility company or a balancing responsible party (BRP) can buy additional power if the forecasted amount turns out to be insufficient for meeting their consumption needs. Structurally speaking, the spot market’s role minimizes risks for power producers and consumers, while guaranteeing the most cost-effective means of power production.

Day ahead

Power for the next day is traded on day-ahead auctions. Usually power is traded for a dedicated hour or quarter-hour interval, but combinations of time intervals can also be traded as blocks. Trading deadlines vary between the different day ahead markets; on the EPEX Spot, the deadline for day-ahead auctions is noon the previous day.

Intraday

On the intraday market, power is traded in quarter-hour intervals for the current day. The lead-time varies between power exchanges but can be as short as five minutes in the case of the EPEX Spot. Read our article about intraday trading.

Renewable power trading – Feed-in Premiums

Renewable power producers are usually too small – in terms of installed power and trading expertise – to directly trade their produced power on energy markets. These trades are usually conducted using an aggregator such as a Virtual Power Plant or a utility company.

To enable renewable energy resources to integrate into the market, various subsidy schemes or Feed-in Premiums (FIP) are used. An FIP is different from what is known as a Feed-in Tariff (FIT). A FIT refers to a subsidy that is paid for feeding-in renewable energy; this power is traded by the TSO or the DSO and effectively means that FITs socialize the risk. A FIP, on the other hand, refers to a subsidy that is paid when power is sold on power exchanges either by the asset owners directly or by a third-party aggregator. FIT and FIP programs differ from country to country. Since only FIPs are directly related to trading power, we will concentrate on FIPs here. FIP schemes can be divided into three distinct approaches. Calculating the amount of a FIP can either be fixed, sliding, or defined by a cap and floor system. A fixed FIP means the premium is always the same amount of money per MWh no matter what current market prices indicate, while a sliding FIP refers to a system that correlates with market price movement. A FIP scheme with a floor and cap falls between the other two models: it protects the asset owner from steep negative prices and protects the FIP provider against extremely high prices.

Since a fixed FIP is independent from the market price, asset owners assume all the risk of market developments. This can result in revenues that are greater or far less than would be the case with a FIT scheme. Often, fixed FIPs have an energy source-dependent factor for incentivizing certain energy types.

Sliding FIPs use a combination of market prices (usually averaged over a certain period, such as one month) and a predefined reference tariff level. Quite often, a technology-specific factor is also calculated into the price. This should relieve some of the risk carried by the asset owner: if market prices are high, the FIP is smaller; if prices on the spot markets are low, the FIP rises. If spot market prices exceed the FIP, no premium is paid. Depending on how the margin between FIT and market price is calculated, additional revenues are possible with peak load operation. For example, if the FIP is calculated using the monthly base price of the power exchange – removing the risk of dramatic shifts in either direction of the feed-in price – a surplus may emerge compared to a steady feed-in.

FIPs are instruments that should help asset owners coordinate power production with price signals from the market to minimize instances of over- or underproduction. FIPs incentivize stronger market integration of renewable assets. Furthermore, FIPs reduce market risks for renewable energies since they provide small-scale power plant operators with a degree of financial security.

More to read

XBID: Cross-European intraday trading

On 12 June 2018, cross-border intraday trade was introduced in the EU between Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Norway, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain and Sweden. Known by its abbreviation XBID, the new mechanism harmonized trading systems and made it possible to coordinate bids from market players in the participating countries and to conduct cross-border intraday trades. However, such trades require enough availability of cross-border transmission capacity.

XBID is essentially a common IT system consisting of a Standard Order Book (SOB), a Capacity Management Module (CMM) and a Shipping Module (SM). The standards are binding for all participants. EU objectives state that the project should facilitate an integrated intraday market and make it more efficient and responsive: With XBID, market participants will have the opportunity to close their balancing groups throughout Europe more quickly, which should lead to lower balancing energy costs. The EPEX SPOT, GME, Nord Pool and OMIE power exchanges as well as the transmission system operators in each participating country are XBID partners.

Disclaimer: Next Kraftwerke does not take any responsibility for the completeness, accuracy and actuality of the information provided. This article is for information purposes only and does not replace individual legal advice.