What does Liberalization and Unbundling of Energy Markets mean?

Definition

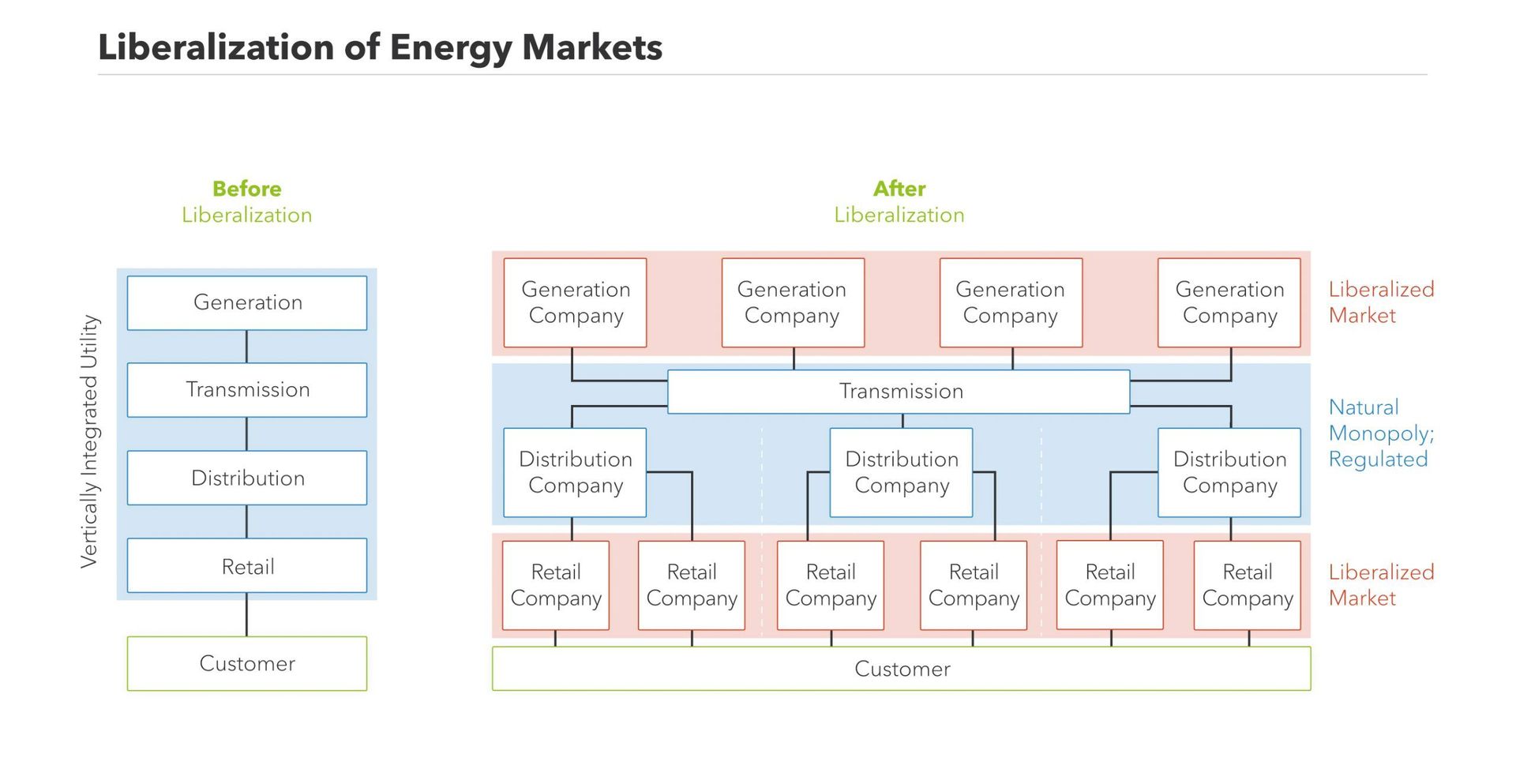

The liberalization of the energy market means the opening of the electricity and gas market to free competition. This has broken up existing monopolies and opened the market to more participants. In most cases, liberalization was accompanied by unbundling, which made a distinction between generation, transmission and distribution/retail in the energy sector. The aim was to make electricity supply more efficient by integrating competitive forces where possible and by integrating regulation where necessary. In Europe, liberalization began in 1996 with the adoption of the first European Directive.

History of the Liberalization and Unbundling of the European Energy Markets

The electricity market with free competition, as we know it today, is still very young and under development. Three decades ago, the European electricity sector was a monopoly. Vertically integrated companies were responsible for generation, transmission and supply of electricity. In the absence of competition, these companies were able to determine electricity prices. Since those companies also held the grid infrastructure, market access of new players was impossible. Incumbent vertically integrated utilities basically were able to act as gatekeepers to the grid.

In 1996 the European Union started to gradually open the market for competition – to liberalize the energy market just like it did before with several other sectors. The legal basis of the liberalization and harmonization of the EU internal energy market are Article 194 and Article 114 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU). The aim was and is to create one single integrated internal European electricity market across all EU member states to reduce overall grid costs and benefit from synergies in the security of supply.

A key step in this process was and is the unbundling of the European power sector with the aim to split up the generation, transmission, distribution and retail activities. As a result of the unbundling process, the vertically integrated companies can no longer both generate, transport, trade and supply electricity while managing the transmission and distribution networks.

This unbundling didn’t happen overnight and is not completely finished today. In the first energy package in 1996, only accounting unbundling was required. It demanded the vertically integrated companies to split up the bookkeeping according to the different activities. This was clearly not enough to create a competitive market.

In the second directive (Directive 2003/54/EC and Directive 2003/55/EC), introduced in 2003, legal unbundling was demanded. It allowed a single company to operate in only one of the activities of the electricity value chain: either generation, transmission, distribution or supply. It also demanded that by 2007 all European customers should have the ability to choose their supplier. But, because the different companies still could be part of the same holding, the owners of those companies still had quite some market power.

In the third revision of the energy package, which came into force in September 2009, the next step towards free competition was made by introducing ownership unbundling. This package is followed by the Energy Union Winter Package in 2016/17, which strives to achieve a fully-integrated, further decarbonized electricity market and ensures security of supply through solidarity and cooperation between EU member states. The third energy package is covered in the following legal instruments: Directive 2009/72/EC and Directive 2009/73/EC, Regulation (EC) No 713/2009, No 714/2009, No 715/2009.

The Current Situation

In an ideal situation, both the generation and supply of electricity are fully competitive activities. It means that none of the companies, which pursue generation activities, can influence electricity prices on the wholesale market by using their market power. This should eventually lead to lower prices for the consumer. Also in the retail market, where the suppliers sell electricity contracts to households, free competition is in the benefit of the consumer. Households now have the choice to pick the supplier that offers them the best tariff and service.

In reality, a perfect competition seldom exists. Especially in industries with large capital investments and large infrastructure – like the energy sector - commercial activities are typically in the hands of a few large companies. For the energy economy, national regulating institutions monitor abuse of market power and quantize the level of free competition with the so-called concentration ratio CR3. An analysis by ACER, the Agency for the Cooperation of Energy Regulators in Europe, revealed for example that the level of market concentration in Italy is still very high, with Enel being the main supplier with a market share of more than 80% in household’s electricity supply.

Infrastructure as a Limiting Factor for the Unbundling

The infrastructure of the electricity grid creates a natural monopoly – very similar to telecommunication infrastructure, railroads, or motorways. It would be almost impossible to build a second grid, since the construction of such a large infrastructure would require a high level of investment and extensive permits.

In order to ensure a reliable operation of the grid and to avoid market power abuse, not only the ownership is unbundled. In addition, the natural monopoly is regulated by an independent regulator. It monitors, for example, the access tariffs that the transmission system operators (TSOs) and the distribution system operators (DSOs) charge to producers, who wish to connect their plant to the electricity grid.

While in Europe most countries secure the electricity supply via a national grid, this is not the case in all countries of the world. Off-grid solutions gain in relevance in many developing countries, particularly to provide cost-effective access to electricity in rural and sparsely populated areas. How these are to be integrated into the energy system and whether this should also lead to a liberalization of the natural monopoly of transmission and distribution is highly controversial.

More information and services

The Example of Italy

In Italy, the TSO is Terna. Whereas the transmission network is operated by only one company, the distribution grid is split up in several geographical areas. The most important example of the overall 135 Italian distribution system operators (DSO) is Enel Distributione S.p.A, which covers over 80% of the Italian electricity demand. The most important local operators are A2A, ACEA, IRIDE, DEVAL and HERA. The national regulator for both electricity and gas markets in Italy is AEGGSI (Autorità per l’energia elettrica, gas e il Sistema idrico). They guarantee transparency and competitiveness of the energy market, defend consumers’ interests, and advice authorities on energy issues.

Liberalization and the Energy Transition

The German Agency for Renewable Energy was able to identify links between the opening of the electricity market and the increase in the share of renewable energie. With liberalization, consumers are now free to choose their electricity supplier and the number of electricity suppliers has increased significantly as a result. The AEE explains this correlation by saying that the dissolution of the old monopolies in the energy industry, which often rely on fossil fuel-based energy production, has paved the way for more innovative and environmentally friendly companies.

Disclaimer: Next Kraftwerke does not take any responsibility for the completeness, accuracy and actuality of the information provided. This article is for information purposes only and does not replace individual legal advice.