How Does Emissions Trading Work?

Definition

The European Union Emissions Trading Scheme, also known as ETS or EU-ETS, is an instrument for reducing greenhouse gas emissions at the lowest possible economic cost. Adopted by the European Parliament and the Council of the EU in 2003, it came into force on January 1, 2005. As of present in 2025, all EU countries plus Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway are participating with more than 10,000 emissions-intensive plants from electricity production and CO2-intensive industries participate in European emissions trading. The ETS is also linked to the Swiss ETS.

History and Legal Basis of Emissions Trading in the EU

As early as the early 1990s, the European Commission wanted to introduce a carbon and energy tax, but failed because member states opposed an EU tax and insisted on national rights of self-determination. In 1997, in the course of the negotiations on the Kyoto Protocol, the EU committed to introducing emissions trading - also favored by the United States - after massive initial opposition from its own delegation. The EU Commission provided the conceptual basis with the Emissions Trading Directive (Directive 2003/87/EC), which came into full force on January 1, 2005.

Practice of Emissions Trading in the EU-ETS

Facility operators which emit CO2 must present a valid ETS certificate for each ton of CO2 they emit. The facilities are allocated a certain quota of CO2 certificates at the beginning of the year. If the CO2 emission exceeds the amount of allocated certificates of a plant, operators have to buy certificates in the emission allowance trading. The ton of carbon dioxide saved, also known as 1 EUA, thus receives a direct monetary value that is determined on the basis of supply and demand.

On April 30 of each year, plant operators must disclose their emissions allowance balance: If the number of allowances does not match the amount of CO2 actually emitted, a penalty of 100 euros per missing EUA is due, and the missing certificate must be submitted subsequently. The disclosed emissions are then used to prepare a forecast for the following year.

Technical Process of Emissions Trading

EU emission allowances do not exist as documents - trading takes place in purely electronic form, similar to electricity trading, both via exchanges and over-the-counter (OTC). The most important trading venues are the ECX (European Climate Exchange) in London, the EEX in Leipzig and the EXAA in Vienna. At 11 a.m., the EEX publishes the so-called Carbix each day, which is the EEX Carbon Index of the spot market price for the CO2 price development in Europe.

EU emission certificates are not globally applicable, but can be offset against other Kyoto Protocol certificates (Emission Reduction Units (ERU), Assigned Amount Unit (AAU), Certified Emission Reduction (CER)) as well as other emission certificates under certain conditions. In addition to certificate trading, countries also have the option of trading CO2 quotas based on bilateral agreements.

Steering Effect through Scarcity of Certificates

In order to have a steering effect, i.e. to actually reduce the amount of CO2 emitted, the quantity of freely available certificates must always be below the forecast emission volume. Alongside a statutory minimum price per metric ton of CO2, this is one of the central parameters of EU emissions trading.

Both factors are subject to recurrent political debate. Weighing up the industrial interest in the lowest possible price per CO2 certificate and the need to limit CO2 emissions is a politically controversial topic. From an economic point of view, however, theories such as the carbon bubble have been recommending the fastest possible withdrawal from CO2-intensive production processes for years already.

Which Plants Have to Participate in Emissions Trading?

The European Emissions Trading Scheme does not currently cover the full CO2 emissions of the participating national economies. Plants from the following sectors are participating, and the range of plants covered is continually expanding:

- Energy: Fossil-fueled power generation plants with an installed capacity of 20 MW or more

- Coal industry: coking plants, refineries and crackers

- Metal industry: iron, steel and aluminum mills, i.a.

- Cement and lime industry as well as gypsum and mineral fiber production

- Glass, ceramics and brick industry

- Paper and pulp industry

- Chemical industry

- Production of technical gases (nitrous oxide, fluorinated hydrocarbons)

- Aviation sector

The participating industries account for about 50 percent of European CO2 emissions and, on average, 40 percent of the CO2 emissions of the participating countries. Worldwide, the ETS covers around eight percent of CO2 emissions, according to the German Environment Agency.

Development of the ETS in Four Phases

The European Emissions Trading Scheme is divided into four phases; upon completion of Phase IV, the Kyoto Protocol targets are expected to be met.

Phase I (2005 to 2007)

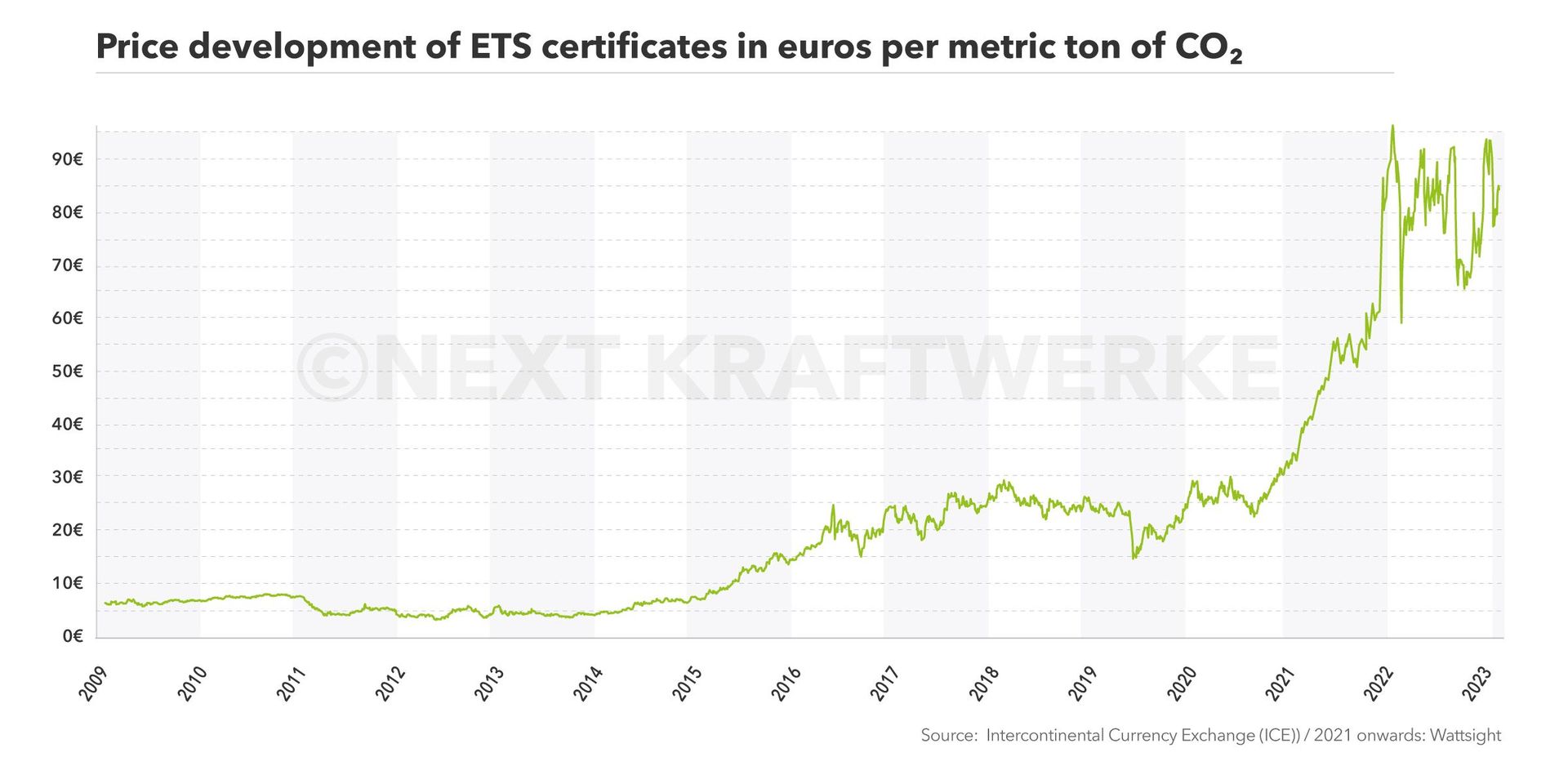

Certificates were allocated almost exclusively free of charge, only five percent of the emission shares were actually auctioned off. The result was a massive oversupply of certificates; the energy sector in particular was oversupplied. There was a considerable drop in prices, with the price tending towards zero at the end of 2007. Nevertheless, even under these difficult circumstances, a study by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Boston recorded a decrease in CO2 emissions within the EU of two and a half to five percent.

Phase II (2008 to 2012)

The second phase was first of all characterized by the inclusion of new countries; in addition to the new EU states of Romania and Bulgaria, these included the non-EU states of Liechtenstein, Iceland and Norway. Furthermore, for the first time there were fewer CO2 certificates provided in this phase than were needed. Missing CO2 certificates now needed to be procured on the world market outside the national territory.

More information and services

Phase III (2013 to 2020)

In Phase III, the EU Commission set an overall EU-wide cap on CO2 emissions for the first time. This amounted to 2.08 billion metric tons of CO2 for 2013 and has been reduced by 1.74 percent annually since then. Fixed CO2 limits per kilogram were set for the production of certain products, so-called benchmarks: the production of 1 kg of steel may thus generate a maximum of 1,328 g of CO2, while 766 g of CO2 may be produced per kilogram of cement. Anything in excess of these quantities must be purchased in emissions allowance trading.

Phase III also marked the transition from the distribution of CO2 certificates to their auctioning: since 2013, twenty percent of CO2 certificates have already been auctioned off, and this figure is set to climb to 100 percent by 2027. Originally, this quota was planned for 2020 already, but the European Council watered it down significantly, not least by the German Federal Government. Deviating from this course, electricity producers have had to purchase all the certificates they need on the market since 2013. To date, some Eastern European countries with a high proportion of coal-fired power generation have been exempt.

The revenues from emissions allowance trading, which have since risen to double-digit billions successfully, are paid out to the member states on the one hand, and transferred to an EU climate fund on the other hand.

Phase IV (2021 to 2030)

For Phase IV, the main aim is to expand and continue the developments initiated in Phase III. In view of the stronger-than-expected global warming, the linear reduction factor for the volume of climate certificates issued increased from 1.7 to 2.2 percent per year - according to the German Environment Agency, however, at least 2.6 percent are required to meet the climate targets by 2030.

Introduction of the Market Stability Reserve

The Market Stability Reserve, also known as MSR, is a reform measure decided by the EU Commission in the course of negotiations on Phase IV of the ETS. It was introduced on January 1, 2019 and is intended to counteract a price decline on the emissions allowance market through an active shortage of emission allowances. This is expected to reduce existing surpluses and avoid the build-up of new overcapacities.

In practice, the market stability reserve intervenes in emissions trading if the market volume falls below or exceeds the tolerance range of 400 to 833 million certificates. In the event of a shortfall, additional certificates are placed on the market; in the event of a surplus, certificates are withdrawn from the market and transferred to so-called MSR funds.

As an enormous surplus of CO2 allowances has built up in recent years, which has been passed down to the next year and thus increased from year to year, the Market Stability Reserve is currently primarily effective in the withdrawal direction: Between 2019 and 2023, 24 percent of the market surplus from the previous year is to be withdrawn each year and added to the MSR funds. Beginning in 2023, the MSR will be limited to the auction quantities of the respective previous year, and all remaining allowances in the MSR funds will be discarded. This aims at preventing a “parking” of emission allowances in the MSR funds, as those “parked” allowances could possibly later be called up and thus lead to emitting CO2 – which would counteract the objective of the measure.

Disclaimer: Next Kraftwerke does not take any responsibility for the completeness, accuracy and actuality of the information provided. This article is for information purposes only and does not replace individual legal advice.